Fans who watched this summer’s semifinals of the Women’s World Cup let out a collective grimace of pain in the first half when Germany’s Alexandra Popp collided with U.S. midfielder Morgan Brian. The two players both went for a header and crashed noggins full force. The impact left both players on the ground, and Popp’s head was gushing blood. Still, after four minutes of medical attention and just one minute off the field, both players were cleared as not having sustained concussions, and allowed to return to the game.

Soccer is among the many sports under scrutiny lately for potential long term damages caused by head injuries. Critics argue that games should have a neutral doctor on hand, as opposed to team doctors who some feel allow players back into play before it’s medically sound to do so. Urging FIFA to change its rules—only three subs are permitted per game, whether or not any player sustains an injury—many fans question whether safety is a top priority on the field.

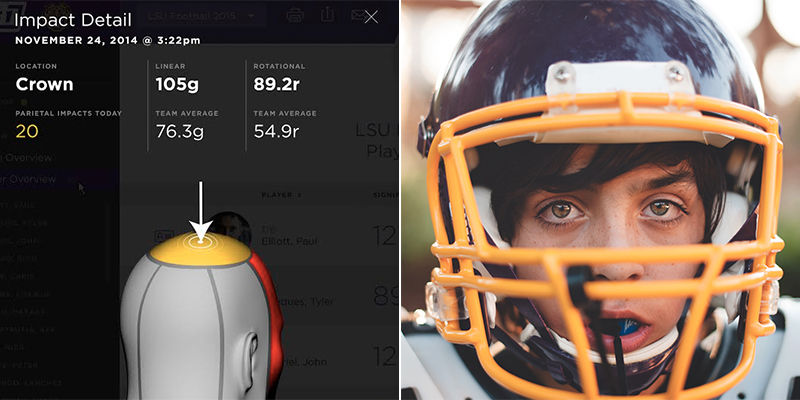

One solution that FIFA would do well to implement is wearable tech that could measure the impact of players’ collisions. Such tools are already being implemented in college football through the company i1 Biometrics, which has developed mouth guards capable of collecting real time cranial impact data. This data is then transmitted to team doctors on site via cloud based technology, allowing them to make more objective decisions as to the severity of a player’s injury. This new technology has the ability to revolutionize the way an athlete’s trauma injuries are diagnosed and treated. The company’s mission statement is driven by some sobering statistics: more than 4 million concussions and brain injuries occur every year from sporting collisions.

While the technology would have to be implemented in a more wearable way for soccer players, who don’t generally wear mouthguards, the strides in measuring cranial impact data should eventually carry over to this sport. In addition to collisions between players, studies have shown that heading the ball can lead to permanent brain damage over time. Last year Scientific American interviewed Robert Cantu, professor of neurosurgery at the Boston University School of Medicine, on the topic. His research has shown that “heading a soccer ball can contribute to neurodegenerative problems, such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy.”

With the issue placed squarely in the news again when millions witnessed the painful collision between two of the Women’s World Cup top soccer stars, it’s more likely than ever that FIFA will have to answer to its critics. In addition to providing neutral doctors, wearable tech like that made by i1 Biometrics—who hope to implement their technology in headbands as well as mouth guards in the future—could revolutionize the way head injuries are treated in soccer, football, and a whole host of other contact sports.

Images via: Flickr/clapstarr; i1 Biometrics