The announcement on Jan. 27, 2021 that two companies, 3D Systems and United Therapeutics Corporation, had successfully bioprinted lungs — organs that, significantly, had vascular structures capable of sustaining them — represented the latest breakthrough in a burgeoning field, and another step toward the day when transplantable 3D organs become a reality.

The companies’ development involved 3D printing vascularized hydrogel scaffolding that can be suffused with living cells, which in turn will create tissue. Dr. Jeffrey Graves, 3D Systems’ president/CEO called the development “absolutely remarkable” in a news release, and his company plans to ramp up development of bioprinting solutions.

Another recent development in this sector saw researchers at Carnegie Mellon University employ a 3D printer to create a model of the human heart. The material that was used in this process, according to a Jan. 7 report on Medical Expo E-Mag, was extracted from seaweed.

Adam Feinberg, a professor of biomedical engineering and materials science at Carnegie Mellon, told Medical Expo that bioprinting a transplantable heart is “decades off,” but added that parts of that organ, like valves and sections of the ventricle, should be available “much sooner and have a major impact in that way in a matter of years.”

Advances like these have become commonplace throughout the medical field in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, which has presented new challenges and demanded innovative answers. But beyond that is the grim reality that there was a crying need for organ transplants, even before the outbreak. Over 108,000 U.S. patients were on waiting lists as of the end of January, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing, and 20 people die every day for lack of a transplant.

But the aforementioned breakthroughs offer hope, as did such 2019 developments as the 3D printing of a rabbit-sized heart in Israel and a pancreas in Poland. There is every expectation that the momentum will be maintained, as indicated by predictions that the 3D bioprinting market size — which encompasses not just organ printing, but that of ventilators, COVID-19 test kits, etc. — will exceed $9.9 billion in 2026, up from $8.3 billion in 2020. That’s a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of nearly 19 percent.

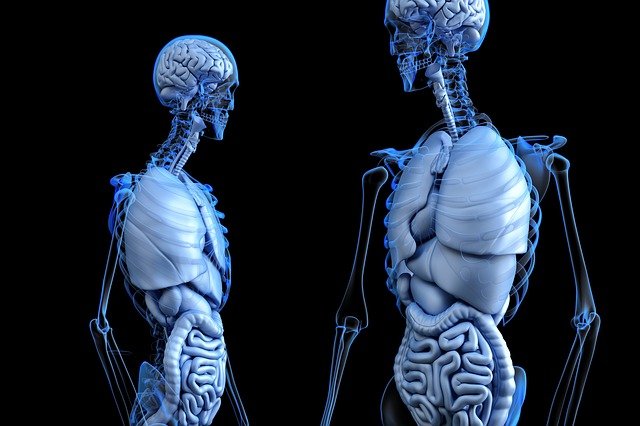

Two of the bigger challenges of creating transplantable 3D organs are differentiation (i.e., ensuring that a patient’s body accepts such organs) and, as mentioned earlier, vascularization. Researchers believe that the first issue can be solved by using the patient’s own stem cells to build a new organ, though Robby Bowles, a bioengineer at the University of Utah, told The Scientist that it’s not that simple — that it’s a matter of “coming together and producing complex patternings of cells and biomaterials together to produce different functions of the different tissues and organs.”

Research is ongoing in that realm, and developments like the one by 3D Systems/United Therapeutics make clear that vascularization is possible. As Courtney Gegg, a senior director of tissue engineering at Prellis Biologics, told The Scientist, a blood supply is vital to organs’ survival.

“It can’t just be this huge chunk of tissue,” she said.

That hurdle, at least, has been crossed, the latest sign of progress in a promising field. These latest developments show that the 3D bioprinting of transplantable organs will one day become a reality.